Life at the National Home, Circa 1922

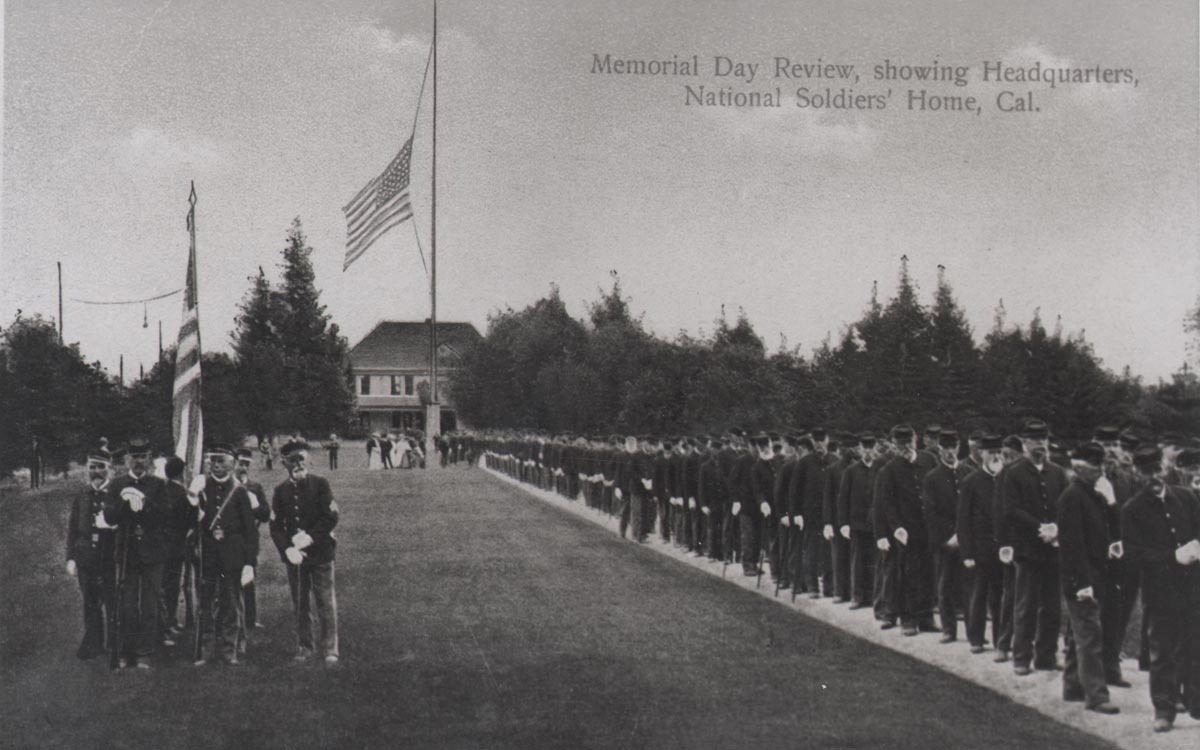

“The Sawtelle Tribune, March 8, 1922Admission to the Soldiers Home is simple. Any honorably discharged soldier or sailor of the army or navy of the United States may gain admission by laying on the adjutant’s desk his certificate of honorable discharge and pension certificate, if a pensioner.

A Place of Peace, Quiet and Contentment

That’s how The Sawtelle Tribune described daily life at the Pacific Branch of the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers.

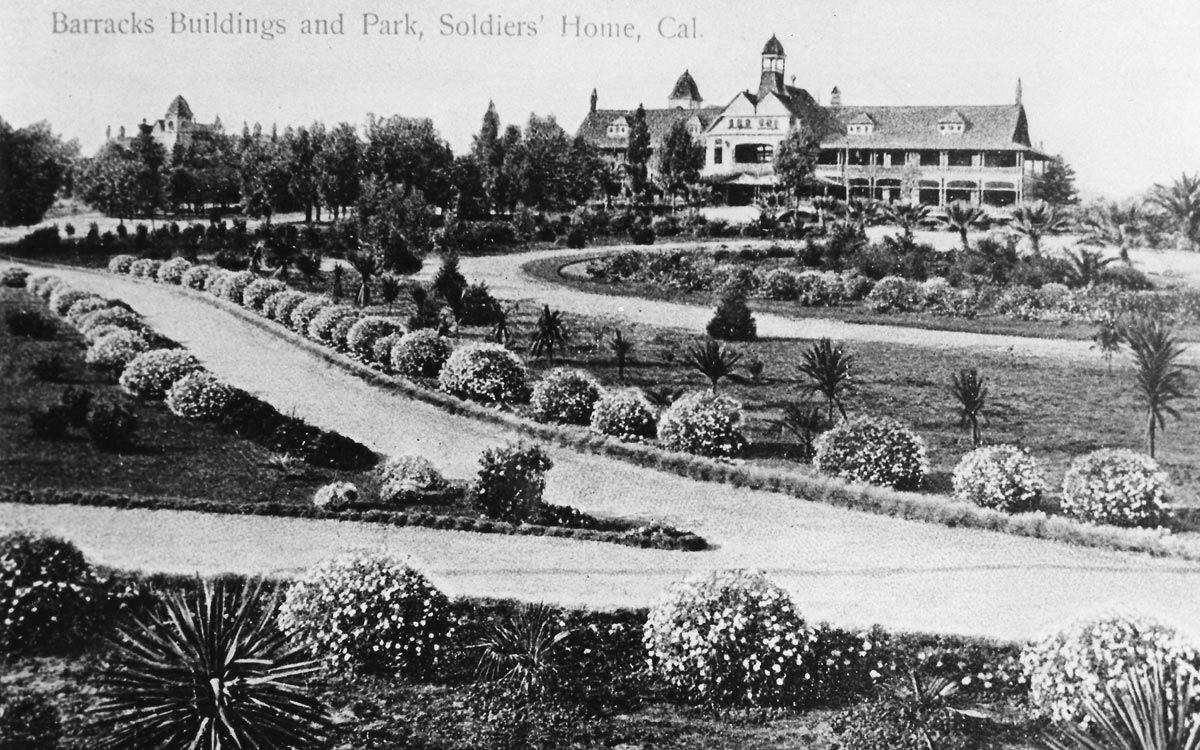

It was place where “every physical want” was supplied. If you lived there, you were given a uniform, a bed and locker in a barracks, three meals a day, free classes, and medical care. You could also live off campus and stop by for a free meal or take a class.

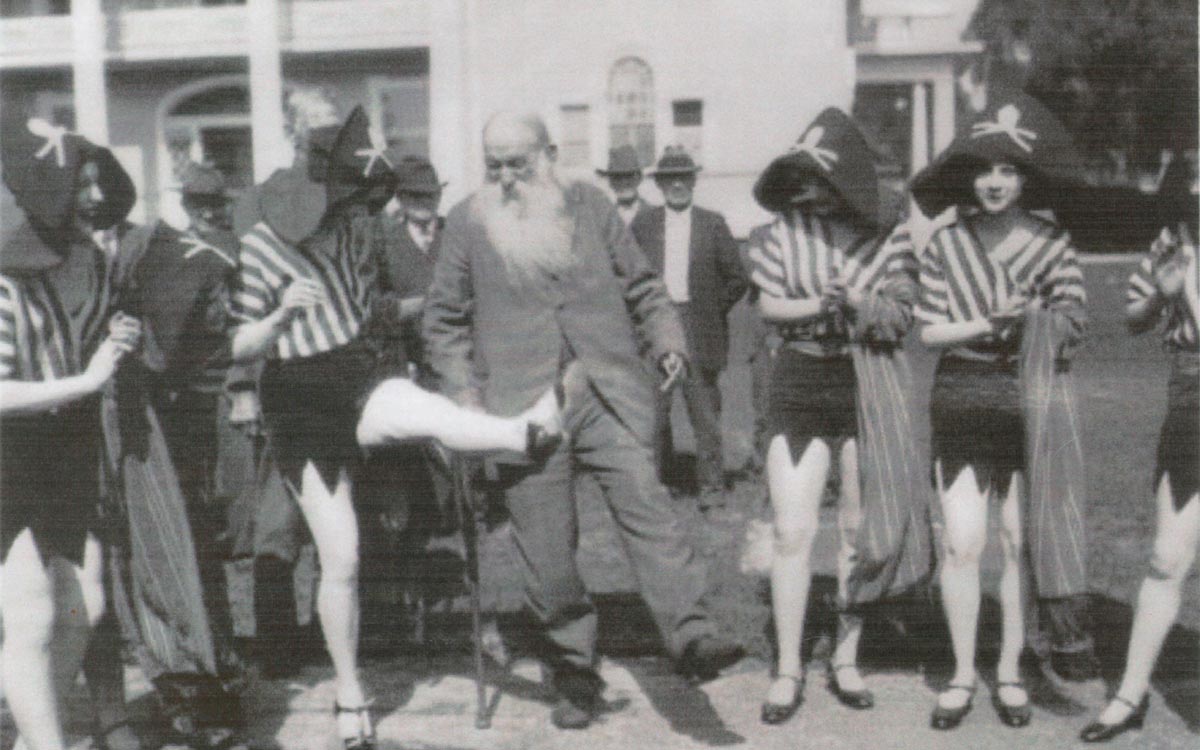

Entertainment? There was plenty of it. Picture shows and vaudeville acts at the 1,000-seat theater. A two-story billiards hall. Library with 10,000 books. And a band and orchestra that drew on the talents of the veterans.

If you were able to work, you held a job on campus or in the community. Veterans on campus were responsible for everything from picking up trash around the grounds to growing the food used in the dining halls.

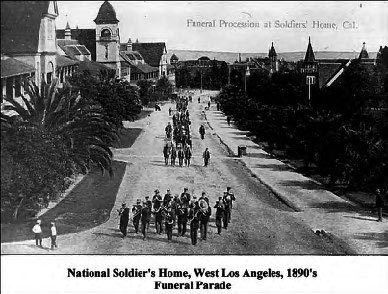

As befitting a military facility, the days were highly regimented, starting with a bugle sounding reveille at 6 a.m. Sick call was at 8 a.m., the flag was lowered during the 4:40 p.m. retreat, tattoo was at 8:00 p.m., and taps were played at 9:00 p.m. Mess calls were sounded five minutes before each meal.

Although the modern-day VA West LA campus is surrounded by the city, the Pacific Branch was out in the country. But the veterans weren’t isolated. There was frequent bus and streetcar service to Los Angeles, Santa Monica, and Venice. The Pacific Electric railway’s trip book to LA was especially popular – 10 rides for $1.50.

Source: “Soldiers Home, Calif.,” by James J. Fitzgerrell, The Sawtelle Tribune, March 8, 1922.